Chaotic Lifestyles, Household Chaos, and Chaotic Attachment: Clinical and Public Health Perspectives

Chaotic Lifestyles, Household Chaos, and Chaotic Attachment: Clinical and Public Health Perspectives

Target audience: addiction professionals, mental health and social care practitioners, and public health audiences.

Abstract

Background: The term chaotic lifestyle is widely used in substance use and homelessness services to describe patterns of living that appear disorganised, unpredictable, and difficult to manage. Parallel research on household chaos and chaotic (disorganized) attachment provides a more precise, measurable framework for understanding how instability in the home and early relationships affects health and behaviour across the lifespan.

Objective: To integrate evidence from public health, developmental psychology, and clinical practice to clarify: (1) what is meant by chaotic lifestyles and household chaos; (2) how these constructs are measured; (3) the role of chaotic or disorganized attachment; and (4) implications for substance use treatment, mental health care, and service design.

Key findings: Household chaos, often measured by the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS), is associated with adverse child, parent, and family outcomes, including emotional and behavioural difficulties, poorer health behaviours, and increased parental stress. Disorganized attachment, frequently rooted in frightening, inconsistent, or neglectful caregiving, is linked to affective instability, interpersonal problems, and higher risk for psychopathology and substance use in adulthood. Chaotic lifestyles in clinical populations typically emerge from the interaction of individual vulnerability, early adversity, structural disadvantage, and service barriers, rather than from “non-compliance” or personality traits alone.

Conclusion: Chaotic lifestyles should not be viewed as fixed personal attributes but as dynamic, modifiable patterns arising within specific environmental and relational contexts. Trauma-informed, flexible, and family-aware interventions that address household chaos and attachment disruptions are likely to improve outcomes in substance use and mental health care.

1. Introduction

In clinical and service settings, people with severe substance use problems, homelessness, or multiple social difficulties are often described as living “chaotic lifestyles.” While this phrase is common, it is imprecise and can be implicitly stigmatising. An evidence-informed approach benefits from distinguishing between:

- Chaotic lifestyles – broad descriptive term for instability in daily life, routines, and social functioning.

- Household chaos – a measurable construct capturing noise, crowding, lack of routine, and unpredictability in the home environment.

- Chaotic (disorganized) attachment – an attachment pattern characterised by contradictory and disorganised responses to caregivers, often linked to early trauma and later emotional instability.

Integrating these concepts helps practitioners move beyond labels and towards specific risk factors and intervention targets that can be assessed, monitored, and modified.

2. Definitions and core constructs

2.1 Chaotic lifestyle (clinical and service usage)

A chaotic lifestyle is not a formal diagnostic category. In practice, the term is often applied when a person’s life appears marked by:

- High levels of unpredictability and crisis (e.g. evictions, arrests, health emergencies).

- Difficulty maintaining routines (appointments, medication schedules, employment, childcare).

- Frequent interpersonal conflict or rapidly changing relationships.

- Co-occurring challenges such as substance use, mental health problems, poverty, and housing instability.

From a clinical perspective, this term should be used cautiously. It risks implying that the person is inherently “chaotic,” obscuring the role of trauma, structural determinants, and inflexible systems. ISSUP and other professional bodies emphasise that many people labelled this way demonstrate considerable adaptive skills in chronically adverse conditions.

2.2 Household chaos

Household chaos refers to the level of disorganisation, noise, crowding, and unpredictability within the home. It captures the extent to which the home environment is characterised by:

- High background noise and frequent interruptions.

- Irregular routines (meals, bedtime, school/work times).

- Limited privacy or space due to crowding and traffic.

- Ongoing time pressure, rushing, and lack of order.

Household chaos is not simply “messiness.” It is a chronic pattern of environmental confusion that has been associated with adverse child, parent, and family outcomes in multiple studies.

2.3 Chaotic (disorganized) attachment

Chaotic or disorganized attachment is an attachment pattern originally identified in infancy and later described across the lifespan. It typically emerges when the caregiver is simultaneously a source of safety and fear (e.g. due to abuse, severe inconsistency, or unresolved trauma). Children may show contradictory behaviours (approaching and freezing, approaching and then fleeing), reflecting a breakdown of a coherent strategy for seeking comfort.

In adolescents and adults, disorganized attachment has been linked to:

- Intense, unstable relationships and “push–pull” dynamics.

- High levels of affective instability and difficulty regulating emotions.

- Increased risk for depression, anxiety, self-harm, and substance use.

- Higher rates of trauma exposure and complex post-traumatic presentations.

3. Measurement of household chaos: the CHAOS scale

The most widely used measure of household chaos is the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS), a brief parent- or caregiver-report instrument originally developed to augment direct observational assessments of home environments. The full version includes 15 true/false items; a six-item short form is also in circulation.

Core features of the CHAOS scale include:

- Construct: “Environmental confusion,” including noise, crowding, disorganisation, and lack of routine.

- Scoring: Higher scores indicate greater household chaos (i.e. less order and predictability).

- Psychometrics: The original validation work reported satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reliability. Subsequent studies have examined factor structure and have used both long and short forms in diverse cohorts (e.g. twin studies, epidemiological cohorts, and intervention studies).

In a systematic scoping review of household chaos and child, parent, and family outcomes, household chaos was most frequently measured using variants of the CHAOS scale, underscoring its central role as an exposure measure in this field.

4. Evidence base: household chaos, health, and development

4.1 Child and adolescent outcomes

Scoping and narrative reviews indicate that higher levels of household chaos are associated with:

- More emotional and behavioural difficulties in children (e.g. hyperactivity, conduct problems, internalising symptoms).

- Lower cognitive and academic performance in some studies.

- Less consistent sleep and dietary patterns, and more problematic screen use.

- Greater parenting stress and, in some cases, harsher or less responsive parenting practices.

Household chaos has been examined as both a direct risk factor and a moderator or mediator of other risks (e.g. poverty, parental mental health, and neighbourhood disadvantage). Longitudinal designs suggest that chronic, rather than transient, chaos may be particularly detrimental.

4.2 Adult health behaviours and chronic disease risk

Emerging public health literature shows that chaotic home environments can disrupt adherence to health behaviours important for chronic disease prevention and management, including:

- Healthy eating patterns and family meals.

- Regular physical activity.

- Medication adherence and self-management of long-term conditions.

- Sleep duration and quality.

Authors have argued that clinicians and health promoters should explicitly consider household chaos when designing interventions aimed at lifestyle change, rather than attributing difficulties solely to lack of motivation or knowledge.

4.3 Beyond socioeconomic status

While household chaos is more prevalent in low-income and marginalised communities, research consistently shows that its effects on outcomes often remain even after adjusting for socioeconomic variables. This suggests that household chaos is not simply a proxy for poverty but a distinct, modifiable environmental risk factor.

5. Chaotic / disorganized attachment and psychological “chaos”

Clinical summaries and psychoeducational resources on chaotic or disorganized attachment synthesise a large body of attachment research and clinical observation. Common themes include:

- Origins: caregiving that is frightening, highly inconsistent, or emotionally unavailable; caregivers who are themselves traumatised or dysregulated.

- Core internal experience: simultaneous craving for closeness and fear of it; confusion about whether others are safe or dangerous; negative core beliefs about self-worth.

- Adult manifestations: volatile relationships, chronic mistrust, self-sabotage, dissociation under stress, rapid shifts between idealisation and devaluation of self and others.

Adults with disorganized attachment are overrepresented in clinical populations, including individuals with complex trauma, personality disorders, and severe substance use disorders. These attachment patterns can contribute to the “chaotic” clinical presentations commonly encountered in addiction and mental health settings.

Contemporary resources emphasise that disorganized attachment can change over time through:

- Consistent, safe therapeutic relationships (e.g. trauma-informed psychotherapy, attachment-based therapies).

- Corrective relational experiences with partners, friends, or family members who are reliable and emotionally available.

- Skills-based interventions targeting emotional regulation, mentalisation, and interpersonal effectiveness.

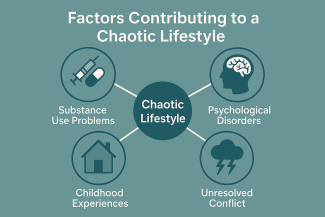

6. Pathways to “chaotic lifestyles” in clinical populations

Bringing together the constructs above, chaotic lifestyles seen in substance use and related services typically arise from the interaction of:

- Individual vulnerability: neurodevelopmental differences, mental health conditions, and substance dependence.

- Early adversity: exposure to violence, neglect, household chaos, and disorganized attachment relationships.

- Structural and social determinants: poverty, discrimination, criminalisation, housing precarity, and lack of access to timely, culturally safe care.

- Service-level factors: rigid appointment systems, fragmented care, and punitive responses to missed appointments or relapse.

In this framework, “chaos” is not an inherent property of the person but the emergent result of multiple interacting risk factors over time. This understanding aligns with trauma-informed, bio-psycho-social and social-ecological models of addiction and mental health.

7. Clinical and public health implications

7.1 Assessment

In addiction and mental health practice, routine assessment could incorporate:

- Brief measures of household chaos (e.g. CHAOS or its short form) to understand environmental constraints on behaviour change.

- Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), trauma exposure, and possible attachment disruptions.

- Practical mapping of daily routines, competing demands, and structural barriers (benefits, childcare, transport, legal obligations).

Such assessments can help clinicians distinguish between “non-adherence” and context-driven barriers, leading to more realistic, collaborative care plans.

7.2 Intervention and service design

Evidence and expert consensus support the following principles:

- Trauma-informed care: prioritising physical and emotional safety, trustworthiness, collaboration, choice, and empowerment.

- Flexibility and outreach: offering drop-in or low-threshold appointments, outreach services, and digital/phone contact options for people whose lives are highly constrained.

- Family- and household-focused approaches: integrating parenting support, household routine-building, and practical problem-solving (e.g. around sleep, meals, school attendance).

- Integrated care: linking substance use treatment with mental health services, primary care, housing, and social support.

- Co-production: involving people with lived experience of chaotic lifestyles, substance use, and household chaos in designing and evaluating interventions.

7.3 Language and stigma

Given the potential for the term “chaotic” to be pejorative, many experts recommend that clinical and recording language:

- Describes specific behaviours and contexts rather than labelling the person (e.g. “currently experiencing high levels of housing instability and household chaos”).

- Acknowledges strengths and adaptive strategies (e.g. “uses multiple informal supports to manage daily survival”).

- Avoids deterministic language that suggests the person is unmanageable or beyond help.

8. Conclusion

Chaotic lifestyles, household chaos, and chaotic or disorganized attachment are interrelated but distinct concepts that help explain why some individuals and families experience persistent instability, high stress, and complex patterns of substance use and mental distress. Research on household chaos demonstrates that the physical and organisational environment of the home has measurable impacts on child and family outcomes. Attachment research highlights how early relational trauma can create enduring vulnerabilities to psychological and interpersonal “chaos.”

For professionals in the substance use and mental health fields, reframing “chaotic lifestyles” as a multi-determined, modifiable pattern – rather than a fixed personal trait – opens up more compassionate, evidence-based, and effective responses. Attention to household environment, attachment history, structural determinants, and service design is essential if interventions are to be realistic, respectful, and capable of supporting long-term change.

References (selected)

- Marsh S, Dobson R, Maddison R. The relationship between household chaos and child, parent, and family outcomes: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):513.

- Matheny AP, Wachs TD, Ludwig JL, Phillips K. Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1995;16(3):429–444.

- Larsen S et al. Measuring CHAOS? Evaluating the Short-form Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale. Collabra: Psychology. 2023;9(1):77837.

- Household chaos: how and why disruptions at home derail healthy habits. Society of Behavioral Medicine, Outlook. 2025.

- MentalHealth.com – Healing From Chaotic Attachment: Can People Change?

- SimplyPsychology – Disorganized Attachment Style

- WebMD – Disorganized Attachment in Adults

- Parenting Across Cultures – Chaos, Order and Hubbub (CHAOS) Scale

- LifeCourse Measurement Library – CHAOS Scale